Percussion Fun!

Everybody loves to make some noise. One year, just to see what would happen, I put a conga in the hallway leading to the classrooms. I wanted to see if anyone could walk by and not give it a tap. The results … maybe on the second pass.

The ability to keep a steady beat is one of the most important musicianship skills we can give our students. As well, the aptitude for rhythm is separate from the aptitude for melody. So, we incorporate a lot of drumming and rhythm instrument activities into our curriculum. These activities are made even more fun when using unusual instruments from around the world. These are a few of the ones we have here at the school.

Tongue drum

Also known as a slit drum or slit gong, the tongue drum is a hollow percussion instrument made from wood. It is shaped like a box, with slits in the top to create resonating tongues. The ends of the box are closed in order to create a resonating chamber, increasing the volume of the sound produced when striking the tongues with a mallet. The instrument can also be played with the fingers. The tongue drum produces a unique and soothing wooden melody.

Also known as a slit drum or slit gong, the tongue drum is a hollow percussion instrument made from wood. It is shaped like a box, with slits in the top to create resonating tongues. The ends of the box are closed in order to create a resonating chamber, increasing the volume of the sound produced when striking the tongues with a mallet. The instrument can also be played with the fingers. The tongue drum produces a unique and soothing wooden melody.

In spite of the name, it is not a true drum but an idiophone. It is used throughout Africa, Southeast Asia, and Oceania. In Africa such drums, strategically situated for optimal acoustic transmission (e.g., along a river or valley), have been used for long-distance communication.

Steel drum

Also known as the steelpan or simply pan, the steel drum is also a member of the idiophone family. It originated in Trinidad and Tobago and is their national instrument. The drum actually refers to the steel drum containers from which the pans are made.

Also known as the steelpan or simply pan, the steel drum is also a member of the idiophone family. It originated in Trinidad and Tobago and is their national instrument. The drum actually refers to the steel drum containers from which the pans are made.

Beginning around 1947, the modern pan has been made from a 55-gallon industrial oil drum. The pitch of the note is determined both by the size of the oval to be struck and the length of the “skirt” of the drum. The pan is struck using a pair of straight sticks tipped with rubber.

The pan is kept in tune using a strobe tuner, much the same as tuning the guitar. There are several ways in which a steelpan may become out of tune, most commonly this is caused by playing the steelpan with excessive force or through incorrect handling. A tuner must have great skill in their work to manage to make the notes sound both good and at the correct pitch. Much of the tuning work is performed using hammers.

Although a relatively recent addition to the percussion family, the steel pan has taken the world by storm. In 1951, the Trinidad All Steel Percussion Orchestra (TASPO), performed at the Festival of Britain. The Esso Tripoli Steel Band, played at the World’s Fair in Montreal in 1967, and later toured with Liberace as well as being featured on an album with him. The Afropan Steel Band was established in Toronto in 1973 by Earl La Pierre as part of the Caribana Festival held annually in that city. We were fortunate to have Earl La Pierre Jr., a world-class solo pannist, perform at our year end recital in 2008.

Although a relatively recent addition to the percussion family, the steel pan has taken the world by storm. In 1951, the Trinidad All Steel Percussion Orchestra (TASPO), performed at the Festival of Britain. The Esso Tripoli Steel Band, played at the World’s Fair in Montreal in 1967, and later toured with Liberace as well as being featured on an album with him. The Afropan Steel Band was established in Toronto in 1973 by Earl La Pierre as part of the Caribana Festival held annually in that city. We were fortunate to have Earl La Pierre Jr., a world-class solo pannist, perform at our year end recital in 2008.

Daf

The daf is a large frame drum used in popular and classical Middle Eastern music. It is considered the national musical instrument of Pakistan.

The daf is a large frame drum used in popular and classical Middle Eastern music. It is considered the national musical instrument of Pakistan.

The daf is an ancient instrument. It can be seen in mesolithic cave paintings dating between 10,000 and 8,000 BC, in an Assyrian Empire relief dating before the 7th century BC, and in many other images dating before the Common Era.

These frame drums were played in the ancient Middle East (chiefly by women in Kurdish societies), Greece, and Rome and reached medieval Europe through Islamic culture. The Arabs introduced the daf and other Middle Eastern musical instruments to Spain, and the Spanish adapted and promoted the daf, as well as instruments such as the guitar, in medieval Europe.

The drum comes in many different sizes, and is usually round. The frame is made of wood, with a membrane that was traditionally made of animal skin, but modern versions use synthetic materials as well. The daf’s unique sound is created by adding things such as bells, rings, chains, cymbals or metal discs to the inside of the frame.

The most common way of playing the daf is to hold it in the left hand while beating the skin with various strokes of the fingers, thumb, palm and heel of the right hand. At the same time, the fingers of the left hand produce additional flicking sounds on the rim of the drum, usually on the offbeat. The drum is also thrown upwards or sideways in a regular beat, causing the rings to jingle.

Initially, I thought that the coordination needed to play the daf would be less than that for the drum kit. I was wrong!

Bodhrán

The bodhrán is a frame drum of Irish origin. Although most common in Ireland, the bodhrán has gained popularity throughout the Celtic music world, especially in Scotland and our Canadian East Coast including Cape Breton, North mainland Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, and Prince Edward Island.

The bodhrán is a frame drum of Irish origin. Although most common in Ireland, the bodhrán has gained popularity throughout the Celtic music world, especially in Scotland and our Canadian East Coast including Cape Breton, North mainland Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, and Prince Edward Island.

The bodhrán is one of the most basic of drums and as such it is similar to the frame drums, like the daf, which are distributed widely across northern Africa, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean region. It consists of a circular wooden frame ranging in size from 25 to 65 cm (10–26 in) in diameter. A goatskin head is tacked to one side, although synthetic materials or other animal skins are sometimes used. The other side is open-ended for one hand to be placed against the inside of the drum head where it is used to control the pitch and timbre. One or two crossbars may be inserted inside the frame, but this is increasingly rare on modern instruments. Some professional modern bodhráns integrate mechanical tuning systems similar to those used on drums found in drum kits, using a hex key to tighten or loosen the skin.

The drum is usually played in a seated position, held vertically on the player’s thigh and supported by his or her upper body and arm. A hand is placed on the inside of the skin where it is able to apply pressure to control the tension (and therefore the pitch and timbre), with the back of the hand resting against the crossbar. The drum is struck with either the bare hand or with a lathe-turned piece of wood called a tipper. Tippers were originally fashioned from a double-ended knuckle bone, but are now commonly made from ash, holly, or hickory wood.

There are numerous playing styles, mostly named after the region of Ireland in which they originated. The most common is Kerry style, which uses a two-headed tipper, while the West Limerick style uses only one end of the tipper.

The bodhrán is a relatively new introduction to Irish music. There are no known references to this particular name for a drum before to the 17th century. Although various drums (played with either hands or sticks) have been used in Ireland since ancient times, the bodhrán itself did not gain wide recognition as a legitimate musical instrument until the Irish traditional music resurgence in the 1960s and 1970s.

The bodhrán is a relatively new introduction to Irish music. There are no known references to this particular name for a drum before to the 17th century. Although various drums (played with either hands or sticks) have been used in Ireland since ancient times, the bodhrán itself did not gain wide recognition as a legitimate musical instrument until the Irish traditional music resurgence in the 1960s and 1970s.

The bodhrán is believed to have evolved in the mid-19th century from the tambourine, which can be heard on some Irish music recordings dating back to the 1920s and viewed in a pre-Famine paintings. It is known that by the early 20th century, home-made frame drums were constructed using willow branches as frames, leather as drumheads, and pennies as jingles. In photographs from the 1940s and videos from the 1950s, jingles remained part of the bodhrán construction like a tambourine, but the instruments were played with a tipper. It has also been suggested that the instruments were often make from the skin trays used in Ireland for carrying peat or from the sieves used in winnowing corn. Today, the bodhrán has largely replaced the role of the tambourine in Irish music.

Flexatone

The flexatone or fleximetal is a modern percussion instrument consisting of a small flexible metal sheet suspended in a wire frame ending in a handle. Although it is indirectly struck, it is considered part of the idiophone family.

The flexatone or fleximetal is a modern percussion instrument consisting of a small flexible metal sheet suspended in a wire frame ending in a handle. Although it is indirectly struck, it is considered part of the idiophone family.

The flexatone can create a variety of sounds, the most iconic of which is the “spooky” glissando effect comparable to the musical saw. They player shakes the instrument causing the plate to be hit alternatively on each side by rubber or wooden beaters mounted on a clock spring. Thumb pressure on the free end of the plate changes the pitch, resulting in a glissando from note to note.

The flexatone was first used in 1920s jazz bands as an effect but is now mainly, although rarely, used in orchestral music. It is sometimes heard in funk music, and occasionally in pop music for special effect. It is occasionally used in the soundtracks of films or cartoons to represent “ghosts” or other paranormal phenomena. In classical music, it appears in the work of Arnold Schoenberg, Hans Werner Henze, Sofia Gubaidulina, and Dmitri Shostakovich, among others.

Vibraslap

The vibraslap is a percussion instrument consisting of a piece of stiff U-shaped wire connecting a wooden ball to a hollow box of wood with metal “teeth” inside. The percussionist holds the metal wire in one hand and strikes the ball against the palm of their other hand. The box acts as a resonating body for a metal mechanism placed inside with a number of loosely fastened pins or rivets that vibrate and rattle against the box.

The vibraslap is a percussion instrument consisting of a piece of stiff U-shaped wire connecting a wooden ball to a hollow box of wood with metal “teeth” inside. The percussionist holds the metal wire in one hand and strikes the ball against the palm of their other hand. The box acts as a resonating body for a metal mechanism placed inside with a number of loosely fastened pins or rivets that vibrate and rattle against the box.

The vibraslap is descended from the African “jawbone”. The lower jawbone of a donkey or a zebra would be used as a rhythm instrument, where the teeth would be scraped like a guiro or struck to make the loose teeth rattle. The Instrument was carried by slaves to South America where it became known as the Quijada.

The vibraslap itself was invented in 1967 by Martin Cohen. It is said that Cohen was told by percussionist Bobby Rosengarden that, “If you want to make some money, make a jawbone that doesn’t break.” Cohen took that concept and invented the Vibraslap. It was the first patent granted to the instrument manufacturing company Latin Percussion.

Once you recognize the sound, the vibraslap can be heard on a number of famous rock songs like “Crazy Train” by Ozzy Osbourne, “Sweet Emotion” by Aerosmith, “Orange Crush” by R.E.M., “A Change of Seasons” by Dream Theater, “Feelin’ Alright” by Joe Cocker and throughout the aptly titled “Donkey Jaw” by America.

Can you hear it on this 1967 US No. 1 hit single “Green Tambourine” by The Lemon Pipers?

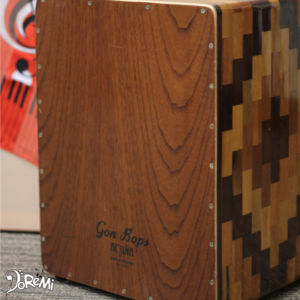

Cajón

A cajón is a box-shaped percussion instrument originally from Peru.

A cajón is a box-shaped percussion instrument originally from Peru.

Five sides of the box are generally made from sheets of 13 to 19 mm (1/2 to 3/4 inch) thick wood. A thinner sheet of plywood is nailed on as the sixth side, and acts as the striking surface or head, which is referred to as the tapa. A sound hole is cut on the back side. The modern cajón may have rubber feet, and screws at the top for adjusting percussive timbre.

Originally the instruments were only wooden boxes, but now they may have several stretched cords pressed against the inside top for a buzz-like effect, resembling a snare drum. Guitar strings, rattles or drum snares can serve this purpose. Bells are also sometimes installed inside near the cords.

The player sits astride the box, tilting it at an angle while striking the head between their knees. The percussionist can play the front, sides, or rear faces with the hands, fingers, or sometimes implements such as brushes, mallets, or sticks.

Since the late 16th century, the cajón has been the most widely used Afro-Peruvian musical instrument. Slaves of west and central African who had been taken to coastal Peru are considered to be the source of the instrument. After the end of slavery in Peru, the cajón spread to a much larger audience, most notably the Criollos. Currently, the instrument is common in musical performance throughout the Americas and Spain. The use of the cajón has made its way into flamenco, rumba and other Latin American genres, and is rapidly becoming popular in blues, pop, rock, funk, world music, and jazz. Because the cajón can simultaneously serve as both a bass drum and a seat for the drummer, it is often used by bands instead of a full drum kit when performing in small spaces.

Balafon

The balafon is a gourd-resonated xylophone, and part of the idiophone family. It is closely associated with the Mandé, Senoufo and Gur peoples of West Africa.

Although quite similar, it is believed to have developed independently of the Southern African and South American instrument we now call the marimba. Oral histories and written records of the balafon go back to at least the 12th century. European visitors to West Africa described balafons in the 17th century that were largely identical to the instrument we see today. The popularity of the balafon has seen a resurgence since the 1980s with the growth of African Roots Music and World Music.

Although they come in a wide range of sizes, a balafon usually has 17–21 keys, tuned to a tetratonic, pentatonic or heptatonic scale, depending on the culture of the musician. Balafon keys are traditionally made from béné wood, dried slowly over a low flame, and then tuned by shaving off bits of wood from the underside of the keys. Wood is taken off the middle to flatten the key or off the end to sharpen it. The keys are suspended by leather straps just above a wooden frame, under which are hung graduated-sized calabash gourd resonators. A small hole in each gourd is covered with a membrane traditionally of thin spider’s-egg sac filaments, but now more usually of cigarette paper or thin plastic film. This produces the balafon’s characteristic nasal-buzz timbre. The instrument is usually played with two gum-rubber-wound mallets.